Know Your Icon's Icons

A brief ode to the try-hards of music

Another peek behind the curtain: I’m eyeball-deep into research for “Prince week,” at this point quite possibly Prince month, to do some articles on the Beyoncé-Prince connections. Admittedly, I wasn’t a superfan before or anything, but diving into the mind and works of genius, of a fearless, relentless creator, has really given me an appreciation for all of my idols. (can you guess which in particular???)

At the same time, sometimes I also feel crazy. Art is so devalued in this country, it can feel odd to be so obsessive about it. Like, who cares if I finish these five different biographies about him??? (HA! Just kidding, it’s more than that!) I’m not exactly curing cancer here. This isn’t a 9-5 job with benefits.

And it can feel indulgent on top of that—it’s not like the world will be devoid of musicians if you don’t ever play a note. There will not be a dearth of music critics. What does it matter?

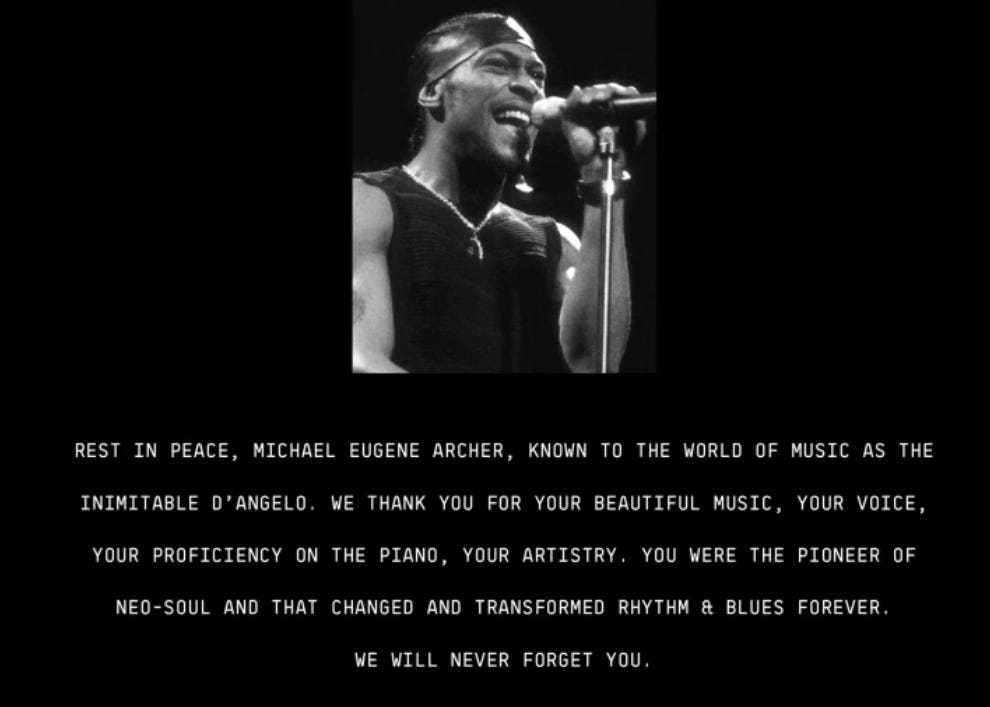

But, like all the greats know, art is culture. It’s legacy. It’s a heritage, and always ours to lose or preserve. I think that speaks to the spirit of Renaissance, to D’angelo, to all great art.

As I watch D’angelo’s 2012 BET awards performance, of course, we see some familiar faces. Beyoncé, and then later Beyoncé and Solange, on their feet and jamming to the funky, upbeat “Sugah Daddy” (not to be confused with Bey’s Suga Mama, released on 2006’s B’day).

Touré, author of two different books about Prince that I’m reading, and also sharer of the é I have to copy and paste into every single article on this stupid website, wrote about D’Angelo’s creative ethos in his tribute to him for Rolling Stone: work hard, study the greats, and treat the art as sacred.

D’Angelo and Questlove were sitting on a couch in a swanky hotel watching, or rather, microscoping a video of James Brown performing in 1964. D and Quest observed every gesture, each dance step and light cue, and anytime the Godfather of Soul subtly signaled the band to do something.

D was on top of the world — a bonafide superstar musician — and even still he was sitting there studying the greats like a hopeful student

[…]

Watching him hyper-analyze older musicians helped me understand some of where D’s greatness came from. He was a serious student of his craft, and a hard worker, even though he was amazingly gifted.

So many soul greats came from, or were heavily influenced by church music. Some, like Aretha Franklin, a preacher’s daughter, found themselves caught between the two worlds, some grappled with it in their work, like Stevie Wonder in Fulfillingness’ First Finale. Later, he spoke about his inspiration as though he were a mere conduit for the art that God inspired. But for others, it could be a delicate balance to figure out how secular the music could get without feeling disrespectful to its sacred origins.

Others had more of a chicken-egg dilemma. Did the music serve God, or did God serve followers through the music? Was it sinful to worship something so worldly as music, or musicians, or a famously sleazy music industry? Or was it something that connected you further?

Even in a secular way, I don’t want to discount the pitfalls of idol worship. Putting people on a pedestal, though perhaps well-meaning, is ultimately a way of dehumanizing them.

But even without a religious affiliation, I find music to be something sacred. The way that one must dedicate oneself to the craft, the history, the ideology, the methods, the ethos of the greats, the saints of sort (Questlove and D’angelo called them “yodas,” according to Touré. The way it moves us through otherwise ineffable peaks and valleys of life. That is devotional. That is, to me, at least, a spiritual practice.

That wasn’t lost on D’angelo, with album titles like Voodoo and Black Messiah. Voodoo, of course, referring to a specifically Black, pre-colonization sense of spirituality. And Black Messiah seemingly a nod to the near 15-year gap between albums, suggested resurrection of that practice. I would also venture to say it’s an allusion to the idea of Black genius, particularly in the conduit for God sense. To honor one’s art and its lineage as holy.

The way Touré describes D’angelo, who grew up in a Pentecostal church, and his attitudes about the music industry, it sounds like a fight for honest musical greatness as a God v. Lucifer-esque forever war.

D’Angelo told me this is how he saw it: Music was becoming overly commercial, and Voodoo was an attempt to push artists away from that toward following the voice inside — wherever it led. Voodoo was also meant to get Prince’s attention, with the hope of convincing the Purple One to collaborate with D and Quest on an album — essentially, to serve as an audition for Prince — but that’s another story.

Kind of ironic—in religious framing, the good vs. evil debate is often about ignoring your innermost desires, feelings, thoughts. But when it comes to the devotionals of music, it’s about embracing them. It’s about speaking the truth, from your soul, to make proper offerings to the greats—such as Prince, another famously defiant force in the music industry.

Rest in power, to a hopeful student who went on to become a powerful teacher himself. Thanks for showing us the power of steady devotion.